OECD comparison: Socio-economic background still a strong influence on educational choices - regional variations in Finland are small

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has published its annual indicator comparing education systems, Education at a Glance. The special theme of this year’s publication was equality in education. The report focused mainly on 2019.

Education enables people of all ages and backgrounds to acquire skills that help them obtain better jobs and a better life.

Both in OECD countries and in Finland, a young person whose both parents are not highly educated is less likely to enrol in upper secondary school and will miss out on an upper secondary education degree more often than average. The lack of such a degree makes people vulnerable in the labour market. In 2020, the unemployment rate of young adults in OECD countries without upper secondary education was about twice that of tertiary graduates.

Children and young people with an immigrant background are generally at a disadvantage compared to their peers in terms of participation in education, and an immigrant background also affects the amount of benefit gained from education in the labour market.

Gender differences are also persistent and impact educational pathways and opportunities in the labour market. In both OECD countries on average and in Finland, boys are more likely than girls to repeat a year, score lower in literacy assessments, and are less likely to graduate from upper secondary school. Boys are less likely to enrol in tertiary education and graduate with a tertiary degree than girls. Men are also less likely to enrol in vocational adult education than women. Despite this, women earn less and have fewer employment opportunities in comparison with men.

There is still a lack of data on the impacts of COVID-19 on education. However, it is already clear that the challenges posed by the pandemic are not evenly distributed. Those already disadvantaged have been hit the hardest, further worsening inequality. Disadvantaged children and young people have often had less opportunities to switch to distance learning compared to their peers. The pandemic has increased the risk of dropping out from school, especially among those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

‘The report shows that Finland must continue determined work to improve the equality of education. Finnish education is still among the best in the world, but inequality is now a real threat to learning outcomes. The work has started, and we are investing heavily in ensuring that each student’s local school continues to be ranked among the best in the world,’ says Minister of Education Li Andersson.

‘Every child and young person must be given the opportunity to succeed, based on their talent and motivation – regardless of family background, place of residence and other factors. During this government’s term, we have, among other measures, improved access to higher education across Finland and investigated obstacles to the accessibility of higher education. However, much remains to be done to achieve this goal,’ says Minister of Science and Culture Antti Kurvinen.

Excerpts from Education at a Glance:

Education gap in favour of women widens

The rise in educational attainment in OECD countries in recent decades has not been evenly distributed, as women in particular have gained ground. The gap in favour of women is particularly evident in tertiary education, but in OECD countries, young men are also less likely to graduate with a secondary degree compared to women.

In Finland, the proportion of women graduates is higher than men in both vocational and upper secondary education. The higher proportion of women with a vocational degree (54%) is explained by the fact that women earn more vocational degrees, and women are the clear majority of graduates over the age of 20. In upper secondary school, the proportion of women graduates is even higher: 58%.

In Finland, 53% of women and 37% of men aged 25-34 had completed a tertiary education degree in 2020.

Gendered educational choices

Gender is strongly linked to the choice of field of study in OECD countries, and Finland is no exception. Comparisons have shown that gender differences in the choice of field of study are often greater in societies that are otherwise considered to be advanced in terms of equality.

In both OECD countries and Finland, women are still clearly less likely compared to men to enrol in STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). In about one in two OECD countries, the proportion of women increased slightly from 2013 to 2019, whilst in others, the trend has been in the opposite direction.

The situation is the opposite in the fields of education and teacher training, where women account for as many as 82% of new tertiary education students in Finland. This proportion is quite close to the current gender distribution of the teaching staff. Men accounted for 26% of teachers across all levels of education. However, the small proportion of male teachers in Finland is not exceptional, as the average in the OECD countries is 30%. The most predominantly female group of teachers are those in early childhood education. In Finland, women account for as many as 97% of this group.

Benefits of education in the labour market are unevenly distributed

Although women are, on average, better educated than men, their standing in the labour market is likely to be worse than that of men. The gap is particularly wide among those without a post-primary degree.

Regardless of level of education, women earn less than men in almost all OECD countries. On average, women in OECD countries earn 76% to 78% that of men’s income.

The size of the pay gap varies depending on the level of education. In Finland, the gap is greatest among tertiary graduates. On average, a woman with a tertiary education in Finland earns 77% of the income of a man with the same level of education.

Socio-economic background influences educational choices

In Finland, the socio-economic status of parents is an even greater indicator of educational attainments than gender. In nearly all countries for which data is available, children of parents with only primary or secondary education are clearly over-represented in vocational education.

In Finland, too, students with a lower socio-economic background are more likely to enrol in vocational education than upper secondary education after completing lower secondary school. In vocational education, 59% of students had neither parent with a tertiary education degree, compared to 27% among upper secondary students.

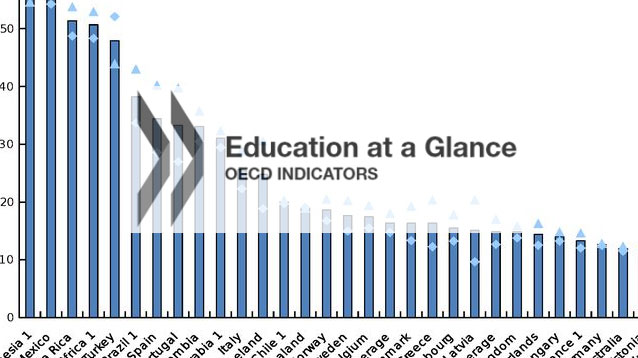

Regional equality in education: In Finland, the differences are small

Regional variations in the level of education of the population are significant in all OECD countries. In the Education at a Glance report, Finland is among the countries where regional variation is the smallest in the comparison, according to a number of indicators. In the case of Finland, the report uses NUTS 2 subnational regions for the analysis, dividing Finland into four regions in mainland Finland and the province of Åland.

In Finland, differences in the percentage of people with a low level of education are relatively small, less than 5 percentage points. Regional variation in the percentage of people with a low level of education is even smaller than in other Nordic countries. Regional variation in the percentage of people with a secondary education is greater (14 percentage points) but still similar to other Nordic countries.

Also in Finland, the highest proportion of tertiary graduates is found in the capital region (Helsinki Metropolitan Area) and Uusimaa: 55% of the adult population. The share of tertiary graduates is clearly lower in Northern and Eastern Finland (42%), with the national average at 48%.

Cost of education per student in Finland fell between 2012–2018

Finland stands out from other countries in that the cost of education per student decreased, whilst in most countries it increased during the same time period. The annual decline in Finland was at a rate of one per cent, whilst at the same time the OECD countries averaged an increase 1.6 per cent per year in spending per student.

In primary and secondary education, costs per student grew by an average of 1.8% annually between 2012–2018. In the majority of OECD countries, more funds were spent per student in 2018 than in 2012. However, Finland was among the five European countries where this trend was reversed: in 2018, the amount spent per student was lower than in 2012.

Despite this, Finland remained above the OECD average in education spending per student remained in 2018 in both primary and secondary education as well as tertiary education. In the OECD comparison, changes in expenditures per student are assessed in real terms, i.e. by taking into account changes in cost levels.

Impact of COVID-19 on education

The effects of the global pandemic have been reflected in almost all areas of life, and education is no exception. The full impact of COVID-19 will not be evident until next year’s report, when statistics for 2020 are available for the indicators.

Starting in March 2020, schools were shut down for various interims in almost all OECD and partner countries. Whilst schools quickly switched to distance learning, the capacity of individual countries to organise distance learning has varied greatly. In addition to differences in capacity, there have also been major variations between countries in how distance learning is regulated and administered. In Finland, education providers have decided on practical arrangements related to distance learning on a fairly independent basis.

Whilst the long-term effects of COVID-19 remain unknown, it is already clear that the pandemic has had a highly unequal impact on people. Those most vulnerable have suffered from the adverse effects disproportionately. In addition, schools have been closed for longer periods of time in countries with poorer learning outcomes.

Governments have provided financial support to help schools cope with the challenges of the pandemic. Two-thirds of the comparison countries reported that they had increased funding for primary and secondary schools. In Finland, too, the government decided in summer 2020 on granting additional funding for early childhood, pre-primary, primary and secondary education. The support is aimed at areas such as remedial teaching and special needs teaching.

The effects of COVID-19 on the economy and working life are reflected in participation in education. The sharp increase feared in the number of young people excluded from education and employment in the first year of the pandemic did not materialise. The share of NEETs (18-24 year-olds not in education, employment or training) in OECD countries increased from 14.4% (2019) to 16.1% (2020). In Finland, the rate grew from 12.8% to 14.8%.

The impact of COVID-19 on participation in education among 25-64 year-olds was significantly greater. Between spring 2019 and spring 2020, participation fell in OECD countries by 27% and in Finland by 15%.

Inquiries:

- Early childhood education and care, comprehensive school education and upper secondary education: Petra Packalen (Finnish National Board of Education), tel. +358 295 331162

- Higher education: Tomi Halonen (Ministry of Education and Culture), tel. +358 295 330095

Education at a Glance reports and links to background statistics are freely available on the OECD website