OECD comparison: In Finland, competition for higher education places is fierce

On Tuesday, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published its annual indicator publication Education at a Glance 2019 comparing education systems around the world. It examines areas such as the level of education, participation in education, education and training costs, the provision of education and training, and the number and employment levels of higher education graduates in the 36 OECD member countries and some partner countries. This year, Education at a Glance includes a focus on tertiary education.

While the participation of Finnish children in early childhood education and care has increased, it still remains below the OECD average.

Children’s enrolment in early childhood education and care has increased in Finland. In 2017, the proportion of children aged 3–5 who participated in early childhood education and care had already reached 79%. However, according to the available figures, one in five 3–5 year-olds remained outside early childhood education and care. In this regard, Finland significantly differs from the other Nordic countries, where participation rates vary from 94% to 98%. Finland is also below the OECD average of 87%.

In all the Nordic countries, investment in early childhood education and care is at a high level in the global rankings, whether viewed from the perspective of expenditure per child or as a percentage of GDP. Early childhood education and care expenditure accounts for 0.8% of GDP in OECD countries and ranges from 1.2% in Finland to 2% in Norway in the Nordic countries.

Number of young people outside work or education drops markedly

The proportion of young people neither employed nor in education or training (NEET) among 20–24 year-olds fell to 14.2% in 2018 from 17% in 2017.

As a result of this decrease, Finland was below the OECD and EU averages in the NEET figures in 2018. Although this decreasing trend is evident both at OECD and EU level, the change in Finland during the year was nevertheless significant in comparison to other Nordic countries. In 2008, 12% of this age group was neither employed nor in education or training in Finland.

Finland invests in students’ welfare services

Finland stands out clearly from other OECD countries in two ways. Compared to other OECD countries, Finland invests significantly more in lower secondary school students and in students’ welfare services.

Finland's spending per student was the third highest at lower secondary level (corresponding to years 7–9 in Finland) among the OECD countries with data available.

There are more teachers per child in Finnish lower secondary schools than in most reference countries, on average nine students per teacher, which is the third lowest ratio among OECD countries. OECD countries have an average student-teacher ratio of 13.

On average, Finland spends relatively more on students’ welfare services than other OECD countries. In addition to teaching, the services offered include healthcare services and school meals, and school transport in pre-primary and primary schools under certain conditions. Education providers are obliged to provide these services to all students free of charge.

Among OECD countries, school meals in particular stand out. A nationwide free-of-charge school meal intended for all pre-primary, primary, lower secondary and upper secondary school pupils is only offered in Finland and Sweden.

Finland differs from other reference countries in the difference between men's and women's graduation rates

The graduation rate describes the proportion of students who start a degree programme and graduate within a certain period of time. In all the countries with data available, the proportion of those who completed a bachelor’s degree within the theoretical duration of the programme was higher among women than among men. In 2017, on average 44% of female students and 33% of male students had graduated within the theoretical duration of the programme. In Finland, the difference between men's and women's graduation rates was the greatest among the reference countries: 27 percentage points.

By adding three additional years to the reference period, the proportion of men graduating in Finland will see the biggest increase in the overall comparison to 64%, while the proportion of women graduating will see a smaller increase, to 79%.

In Finland, expenditure on education and training as a percentage of GDP is higher than in the reference countries

In 2016, education expenditure accounted for 5.5% of Finland’s GDP. The share was higher than the OECD and EU23 average.

According to Education at a Glance, countries invest in education because it is seen to help promote economic growth, enhance productivity, contribute to personal and social development and reduce social inequality, among other reasons. Among OECD countries, education is valued differently and the financial resources invested in it vary.

Expenditure per student

Expenditure per student in comprehensive school education, both for primary and lower secondary levels, increased in Finland at current prices from 2015 to 2016. Average spending per student decreased both in OECD and EU23 countries in primary schools and in OECD countries in lower secondary schools.

In 2016, spending per student also increased in Estonia, and among the Nordic countries in Sweden and Iceland. By contrast, in Norway, where the cost of education has long been among the highest in the OECD countries, expenditure per student in primary and lower secondary education decreased.

In Finland, the number of international students exceeds the OECD average

In 2017, a total of 5.3 million people worldwide studied abroad for a tertiary degree, the majority of them, 3.7 million, in OECD countries. Globally, the number of internationally mobile students in tertiary education has increased in 20 years, and the OECD estimates that the number of students studying abroad will continue to grow. There are many factors behind this: knowledge-based economies need skilled labour, not all national systems are able to meet the demand for education, and studying abroad offers an opportunity to get a good education and find employment. In Finland, too, the Vision of Higher Education and Research for 2030 emphasises international access to higher education and the global attractiveness of higher education.

In 2017, international students represented 8% of Finnish tertiary students, compared with 6% seven years earlier. In Finland, the percentage of international students remains above the OECD average (6%). However, they account for 9% of students in EU23 countries, a slightly higher share than in Finland. Among Finland’s neighbours, Denmark has a higher proportion of international students (11%), followed by 8% in Estonia, 7% in Sweden and 3% in Norway.

Fierce competition for Finnish higher education places

The expansion of tertiary education has continued for a long time in OECD countries. Participation in tertiary education has increased as a larger proportion of young people complete an upper secondary qualification and are eligible to apply for tertiary education. The opportunities for success in the labour market associated with a degree also increase demand for tertiary education.

In around half of the countries, candidates apply directly to higher education institutions; whereas in the other half, applications are submitted through a centralised system, either as the only channel or alongside a direct application process. Several countries do not have data available on tertiary education admissions, so the comparison is not comprehensive.

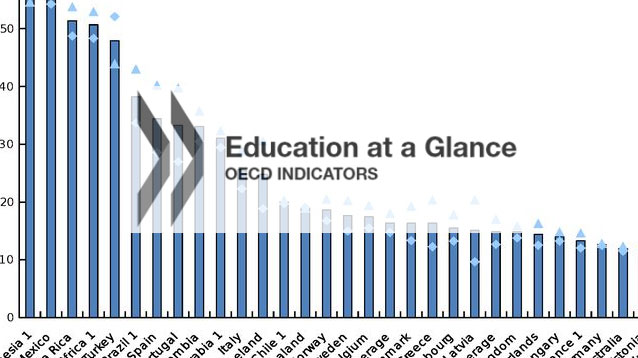

In the majority of countries with data available, all eligible applicants will be admitted to tertiary education. While the open admission system does not necessarily apply to the entire tertiary education sector, students are admitted without selection to at least some higher education institutions or fields of study. Less than half of the systems are selective in the same way as in Finland, where admissions are restricted for all fields of study and all higher education institutions and only some of the applicants are admitted.

Applicant selection is usually based either on an upper secondary final examination or on university entrance tests. Other criteria, such as the average grade of the applicant’s upper secondary school certificate, the applicant’s interview, or work experience are also often taken into account in the selection process.

There are major differences between countries as to the percentage of applicants admitted in a given year. In Finland, two thirds of applicants are left without a place in tertiary education every year. This is the highest rate of rejection among the reference countries. However, competition is almost as fierce in Sweden.

However, it should be noted that the comparison only concerns selectivity in admittance to tertiary education. In some countries, the selection takes place at a later stage, when those who fail in the tests or who progress too slowly in their studies have to drop out of the programme.

In Finland, just under one in five of new entrants to tertiary education had graduated from general or vocational upper secondary school in the same year. Streamlining the transition to tertiary education is one of Finland’s objectives.

Tertiary education graduates account for 41% of the population – the tertiary education graduation rate exceeds the OECD average

According to the target set in the Vision for Higher Education and Research, by 2030 half of 25–34 year-olds will have obtained a degree. In Finland, the proportion of tertiary graduates has risen only slightly over the past 10 years.

Finland is below the OECD average, with the percentage of tertiary graduates having risen by 3 percentage points from 2008 (38%) to 2018 (41%). Over the same period, the OECD average has risen by as much as 9 percentage points from 35% to 44%.

In Finland, students start tertiary education later than on average in OECD countries and the proportion of students starting tertiary education in young cohorts is slightly lower than the OECD average. Due to these factors, the share of tertiary graduates in Finland is lower than the OECD average.

The average age of new entrants (to bachelor’s degree programmes) is 24 years in Finland, compared with the OECD average of 22 years. In the other Nordic countries, too, students enter tertiary education later than elsewhere. In Sweden and Denmark, the average entry age is 24 years, and in Norway 23 years.

By contrast, the tertiary graduation rate in Finland is higher than the OECD average. In Finland, 43% of students completed a bachelor’s degree within the theoretical duration of the programme (the OECD average was 39%) and 73% completed a degree either within the theoretical duration period or during the following three years (the OECD average was 67%).

The employment rate of those without upper secondary education has decreased

In Finland, as in other countries, employment rates have declined over the past decade. In Finland, however, the decline in employment has mainly affected low-skilled workers. Employment among tertiary graduates aged 25–34 decreased by 2 percentage points between 2008 and 2018. Over the same period, the employment rate of those without upper secondary education decreased by 20 percentage points (from 69% to 49%). The employment rate in Finland among young adults who have completed upper secondary education is below the OECD average, but in the same age group the employment rate among tertiary graduates is above the OECD average.

Having a doctorates increases employment prospects in Finland

In 2017, 1.2% of those aged 25–64 had a doctorate in Finland, slightly above the OECD average (1.1%). For comparison, in Switzerland 3.2% of the population has completed a doctoral degree. The employment benefit a doctorate brings varies between OECD countries. In Finland, it is 10% higher when compared to those with a master’s degree, whereas the OECD average is 5%.

Doctoral studies begin later in Finland than in other OECD countries on average. The median age of entrants to doctoral programmes is 31 years, whereas the OECD average is 29 years.

- - -

Inquiries:

- Early childhood education and care, comprehensive school education and upper secondary education: Kristiina Volmari (Finnish National Agency for Education), tel. +358 2953 31276

- Tertiary education: Jukka Haapamäki (Ministry of Education and Culture), tel. +358 2953 30088